A sign is anything that represent something else. Signs create meaning, but what exactly do they mean? What do they communicate and will everyone who interprets the same sign take away the same meaning from it?

The last couple of weeks I’ve been talking about semiotics as part of a larger series about iconography. I offered an introduction to semiotics and signs and then talked about the different categories a sign’s form might take.

Today I want to talk more about the meaning of signs, specifically what a sign’s form literally denotes and what it implicitly connotes.

What are Denotation and Connotation?

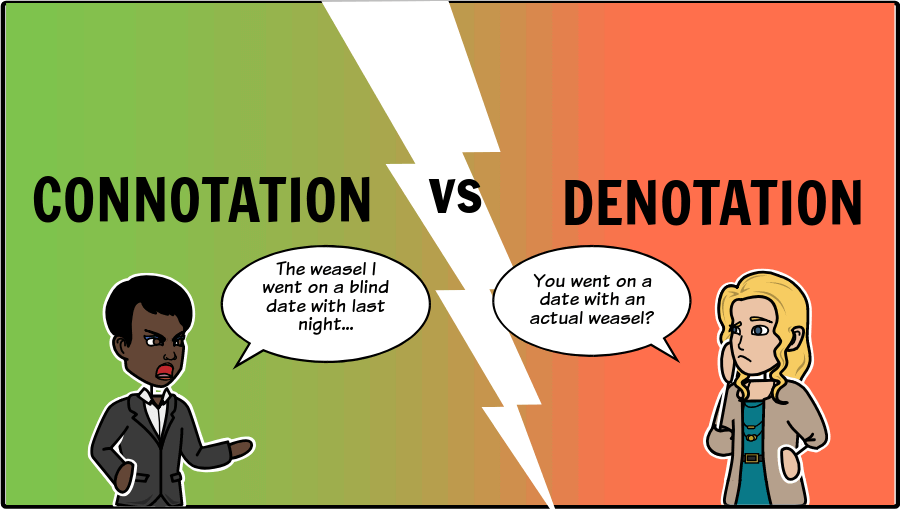

Denotation and connotation both describe the relationship between a signifier (a sign’s form) and what is signified (what a sign represents), though each describes a different meaning.

- Denotation describes the literal meaning of the signifier

- Connotation describes a secondary meaning of the signifier

For example with the word “rose” or an image of a rose the denotation is a type of flower. A connotation of the same sign could be love, romance, or passion. The first is a literal representation, while the second is an implied representation.

You can think of denotation and connotation as different levels of representation or meaning. Denotation is the first level. It’s the dictionary definition. It’s what you literally see. Connotation is the second level and beyond. It’s an idea or feeling that’s invoked by the literal meaning. It’s the emotional associations you make with the signifier and not a literal interpretation of what the signifier represents.

American politics likes to compare Wall Street to Main Street. The denotation of each would be an actual street named either Wall or Main. The connotation of Wall Street is money, wealth, and power, while the connotation of Main Street is regular people with small town values.

The word home has a denotation of a physical structure where someone lives and a connotation of comfort, security, and family.

Connotations are the main part to how we understand signs. We won’t, however, all have the same connotations when we interpret the same signs. Connotations require context and context is built from our unique experiences, ideologies, schemas, and mental models. Because we have different experiences and mental models, it means different people can interpret the same sign in different ways.

Codes as a Context for Interpreting Signs

Ferdinand de Saussure said signs aren’t meaningful in isolation. Meaning comes from interpreting signs in relation to each other. For example every word you’re reading right now is a sign with meaning. In fact every word is a sign made up of individual signs in the letters they include.

By themselves the letters aren’t particularly meaningful, but when they’re combined they form words that take on meaning. The meaning of the words changes based on how I’ve combined them and the order in which I did. The English language serves as a context for reading this post.

In semiotics terminology, this context comes from what are called codes. Codes provide frameworks for making sense of signs. They’re a set of conventions for communicating and interpreting meaning.

Language is a common code that enables those who know the language to communicate with each other, to transfer meaning from one to the other. Signs are most effective when the creator and interpreter both speak the same language. In other words when they use the same code.

You probably hold a group of related ideas about what it means to be either masculine or feminine. The group of ideas is a code.

Codes help us make sense of the world. We learn to understand the world through the dominant codes and conventions present within the culture we live. They’re systems of meaning or belief systems that help us simplify the signs we see to make it easier for them to communicate. These systems or maps allows us to limit the possible meaning of a sign in order to more quickly interpret it.

We interpret signs based on the codes we think apply to it. In fact you might think of creating an effective sign as using the right cues to get the interpreter to apply a certain code.

Hollywood westerns in the 50’s typically had the good guys wearing white hats and the bad guys wearing black hats. The practice was later dropped, but the white hat, black hat code still exists. Look no further than the world of search engine optimization in which people are often described as wearing a certain hat color based on how much their practices is seen as good or bad in the judgement of search engines.

One thing to keep in mind is that codes are dynamic. They can and do change over time. It’s unlikely you hold the exactly the same beliefs you did 10 years ago. You’ve experienced more in that time and so your context has grown and changed.

Types of Codes

One of sites I’ve leaned on for this series on semiotics was created by Daniel Chandler for his students at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth. He offers three types of codes common to media, communication, and cultural studies.

- Social Codes — verbal language, body language, fashion, and rituals.

- Textual Codes — aesthetic codes and codes around different genres and styles.

- Interpretive Codes — idealogical codes such as individualism, capitalism, socialism, objectivism, and most any other “ism” you can think of.

Interpretive codes also include perceptual codes such as the gestalt principles of perception. The idea behind gestalt theory is that some features of human visual perception are universal and that we may all be inclined to interpret certain ambiguous images in the same way.

Closure for example suggests we’re all likely to see an arrangement of individual elements as part of some recognizable whole instead of seeing them as an arrangement of individual elements.

To semiotics these principles are seen as making up a code about visual perception. Gestalt theory isn’t the only connection.

Because signs need context for interpretation and because the interpreter needs a code to understand the meaning of a sign, not everyone seeing a sign will hold the proper context to interpret it as intended.

Design trends (any trend really) like skeuomorphism and flat design are popular, albeit temporary codes. The change from one trend to another might be seen as redefining the popular code.

The medium being used for communication can influence what codes are used by both the creator and interpreter of a sign. Many of the codes in a new medium evolve from codes related to existing media. Hence, skeuomorphic detail in computer interfaces. The details evolved from the details of more physical mediums.

Closing Thoughts

Signs often carry a literal meaning as in the picture of a rose to represent an actual rose. They can also carry an implied meaning such as the image of a rose representing love or passion. The literal meaning of a sign is what it denotes, while the implied meaning is what the sign connotes.

These meanings, particularly the implied meanings require the interpreter of a sign and the creator of a sign to share the same context if the meaning is to be interpreted correctly.

This context comes from codes which are systems of meanings or belief systems that help us limit possibilities in order to find meaning more efficiently.

The most effective communication comes about when a sign’s creator and interpreter hold the same codes. This suggests that before you can really communicate, you should understand your audiences as best as you can. You should understand the codes they have because those codes will be the context in which your communication is interpreted.

Next week I’ll continue and talk about two ways signs can relate to one another to communicate more than they could alone. I want to talk about the syntagmatic and paradigmatic relationships of signs.